Russ McDonald’s statement that “Shakespearean tragedy depends on a paradox” could not be better suited to any other play than in Macbeth[1]. The actions and the structure of the play hinge on the paradoxes found in accepted truths, language, and signifiers. The theme of duality, in particular, comes into special significance in Macbeth. Shakespeare utilizes duality as a tragic motif in Macbeth; that is, it is used to contextualize and procure Macbeth’s hamartia, and also to lead the hero eventually to his downfall and death. Theories from Friedrich Nietzsche’s essay “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense” and Sigmund Freud’s “The ‘Uncanny’” would help us further understand the significance of duality in Shakespeare’s play.

The theme of duality is uncannily pervasive in Macbeth,[2] as is depicted in the diction of the characters. The witches “speak in paradoxes: ‘When the battle’s lost and won,’ ‘Fair is foul, and foul is fair’ (1.1.4,11),”[3] “Double, double, toil and trouble” (4.1.10). The human characters themselves speak at times through duality if not in paradoxes: “All our service / In every point twice done, and then done double” (1.6.15), “Hear it not, Duncan, for it is a knell / That summons thee to heaven or to hell” (2.1.64-65). Macduff, moreover, makes note of “such welcome and unwelcome things at once / ‘Tis hard to reconcile” (4.3.139-140). This extensive use of duality and paradox serves to reflect the play’s consciousness of and emphasis on the arbitrariness of language and words as signifiers.

Indeed, Nietzsche describes words as having “arbitrary assignments…beyond the canon of uncertainty” and “arbitrary differentiations”, explaining that “we believe we know something of the things themselves when we speak of trees, colors, snow, and flowers; and yet we possess nothing but metaphors of things, which do not at all agree with the original entities.”[4] The human being’s “arrogance associated with knowing and feeling,”[5] as Nietzsche terms it, is tested in Macbeth, where Hecate remarks that “security / Is mortals’ chiefest enemy” (3.5.32). To be secure in the stability of language in Macbeth is to forget that “truths are illusions that have become worn out and sensuously powerless.”[6] Macbeth, who, in the beginning of the play, is “sensitive and aware”[7] of the arbitrariness of language—for in fact he notes that “two truths are told (1.3.128) which “cannot be ill, cannot be good” (1.3.132)—in the end forgets the instability of words and signifiers, that they “speak metaphorically or metonymically to a single aspect of the signified; they cannot convey its essence.”[8] Macbeth perceives the admonitions of the apparitions only in their literal sense, and confidently declares that they “will never be” (4.1.94). He forgets Banquo’s warning that “the instruments of darkness tell us truths, / Win us with honest trifles, to betray’s / In deepest consequence” (1.3.123-126). This situation William Scott explains thus: “In becoming a part of the self-deluding show and undoing some literalisms to confirm another, he [Macbeth] skews the boundaries of literal and figurative and of perceiver and perceived, with paradoxical results.”[9] As much as Macbeth, in self-delusion, “skews the boundaries of literal and figurative”, the witches do so as well, if not better, using Macbeth’s ambition-driven over-assurance in language to deceive him who so readily would be deceived. Accordingly, the witches’ use of seemingly impossible predictions and “hopeful messages”[10] effects the dissolution of Macbeth’s awareness of the arbitrariness of language: he who, being unprepared, thus becomes a servant to defect[11]. Hence Macbeth declares ironically that “damned [be] all those that trust them” (4.1.139), not realizing that he himself belongs with the damned.

Macbeth’s defective action, then—his hamartia,[12]—is precisely that he blindly disregards the existence of dualities in the realm of the play. This gives him a false and unhealthy sense of security as, after saying, “I cannot taint with fear…. / The mind I sway by and the heart I bear / Shall never sag with doubt nor shake with fear” (5.3.3,9-10), Macbeth, in response to the servant’s entry, and in what is consequently an expression of his paranoia, says “The devil damn thee black, though cream-faced loon! / Where got’st thou that goose look?” (5.3.11-12). This sense of security is, in turn, haunted by the duality that Macbeth overlooks, and such effects Macbeth’s tragic recognition and reversal.

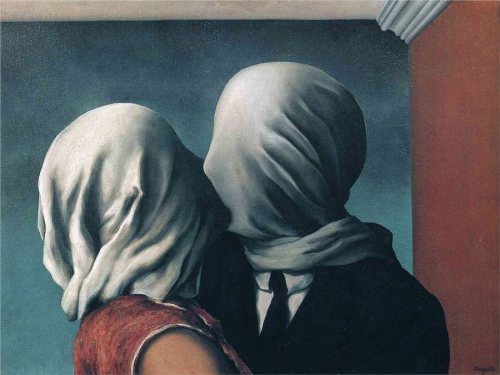

Informing and qualifying the notion of this haunting duality in Macbeth is Freud’s concept of the “double”[13]. In Macbeth there can be found characters whom Freud would identify as the “doubling, dividing and interchanging of the self.”[14] In fact, two stages of Freud’s “double” are represented in the play: that which “was originally an insurance against the destruction of the ego, an ‘energetic denial of the power of death,’”[15] and that which, “from having been an assurance of immortality…becomes the uncanny harbinger of death.”[16] The titular character of the play possesses three of these “doubles” in the figures of Lady Macbeth, the witches, and Macduff—and these figures offer Macbeth unique stages of his own recognition and reversal..

Lady Macbeth, as one of Macbeth’s “doubles,” figuratively completes him, exhibiting characteristics and performing actions that are either opposite or almost like his. In Act 1 Scene 5, she calls on the spirits (l. 40) to “take [her] milk for gall” (l. 48), since her husband is “too full o’th’ milk of human kindness” (l. 17). Her apostrophe to night beginning in line 50 of the same scene, resembling that of Juliet’s in Romeo and Juliet[17], is echoed by Macbeth in Act 3 Scene 2 when he calls on, “Come, seeling night” (l. 49). They both find themselves reluctant before the execution of their murderous actions, yet Lady Macbeth’s power over Macbeth’s identity earlier on in the play is such that he attempts to affirm his masculinity through Lady Macbeth so much so that “he sins to win her approbation.”[18] She inevitably corrupts his masculine identity by using it against him during his times of hesitation. Eventually Macbeth becomes “in blood / Stepped in so far that, should [he] wade no more, / Returning were as tedious as go o’er” (3.4.137-139). Lady Macbeth realises only too late that “What’s done cannot be undone” (5.1.68). When it becomes her turn to regret the actions of herself and her husband, telling him “You must leave this” (3.2.39), Macbeth only informs her of a forthcoming plan for her to “applaud the deed” (3.2.49). Such has become of the situation of Macbeth’s identity as it relates to Lady Macbeth, that his actions have become mere performances, “deeds”, that need the applause of his one audience, his wife. Her death consequently triggers his speech in Act 5 Scene 5 wherein life is but “a poor player / That struts and frets his hour upon the stage / And then is heard no more” (ll. 24-26) – a description of life that is very much pertinent to his own.

Realising such a fact, Macbeth “turns unsuccessfully to the witches for the power he needs to make him author of himself.”[19] The witches, who are characteristically duplicitous, symbolise Macbeth’s “double” that is supposed to assure him of immortality. They are beings who may be figuratively associated with Macbeth. Macbeth’s first words “So foul and fair a day I have not seen” (1.3.38) echo the witches’ last ones in Act 1 Scene 1 where they say “Fair is foul, and foul is fair” (1.1.11) Cheung observes this of the witches’ interaction with Macbeth:

Significantly, it is not a surprise encounter but a meeting that is to take place. Already there is a hint of intercourse between the witches and Macbeth, so what seems to be an external temptation also can be interpreted, as many critics have done, as a psychological projection.[20]

The witches not only embody the external “multiplying villainies of nature / [that] Do swarm upon him” (1.2.11), but also they symbolize the internal, “black and deep desires” (1.4.51) already present in Macbeth’s character. Viewing their relationship thus makes it easier to relate such a relationship with Freud’s idea of the double where “the one possesses knowledge, feelings and experience in common with the other.”[21] Indeed, the witches prove to be effective because, according to Scott, “they seemed to have access to the frightening secrets of his heart.”[22] The power in the duality of their nature, being representative of both the external and internal forces of evil that besiege Macbeth, makes it highly difficult for Macbeth to resist the temptation of accessing and utilizing the murderous ambition that their prophecies leave as a readily-available option for him. However, it is exactly this duality in nature that opens up and leads Macbeth to his downfall. He recognises that he has fallen into this pitfall, but only too late: “And be these juggling fiends no more believed / That palter with us in a double sense, / That keep the word of promise to our ear / And break it to our hope” (5.8.19-22).

In the face of this realisation, Macbeth finds himself pitted against Macduff, the “double” who is the “uncanny harbinger of death” for Macbeth. For, being what Campbell terms as a “figure of the tyrant-monster”[23], Macbeth’s presence inevitably calls for “the redeeming hero, the carrier of the shining blade, whose blow, whose touch, whose existence will liberate the land.”[24] And Scotland must needs be liberated from Macbeth, as it is described by Lennox as a “suffering country / Under a hand accursed” (3.6.49-50). Indeed, Macduff becomes for Macbeth “a thing of terror,”[25] who tells him: “Despair thy charm, / And let the angel whom thou still hast served / Tell thee, Macduff was from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripped” (5.8.13-16)[26]. Hence is Macduff qualified to be the nemesis of Macbeth, whereby he is also portrayed as a figure that is the direct opposite of Macbeth, a figure of “the self-creating and invulnerable masculinity that Macbeth cannot fashion for himself.”[27] Macduff’s character moreover serves to haunt Macbeth with the duality that the tragic character forgets persists in the play’s dramatic universe. The very fact of Macduff’s birth and existence, the circumstances of which Macbeth deems impossible, shakes Macbeth out of his self-inflicted tragic delusion and reverses his expectation of the witches’ equivocal prophecy. His death in the hands of Macduff symbolises the taking-over of the “double”: the former, suffering self, represented in Macbeth, is replaced by the projected and more perfect – though not entirely unscathed[28] – self in the person of Macduff[29].

This ending for Macbeth is not to be restricted with a tragic affect. “Tragedy is the shattering of the forms and of our attachment to the forms,”[30] writes Joseph Campbell. Macbeth, in this light, is at once tragic and liberating. The titular character is tragic because he, blinded by ambition, undermines if not forgets about the existence of duplicity and the prevalence thereof in the world he lives – but on the same note, this selfsame duplicity allows for the liberation of the imprisoned and corrupted self in Macbeth and transfigures it into the more complete, more heroically-realised self in Macduff.

[1] R. McDonald, The Bedford Companion to Shakespeare: An Introduction with Documents (Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin’s: 2001), 86.

[2] All quotations from Macbeth are taken from D. Bevington, The Necessary Shakespeare (The University of Chicago: 2013), 710-747.

[3] D. Bevington, The Necessary Shakespeare, 712.

[4] F. Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense,” in The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, ed. David H. Richter (Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin’s: 2007), 454.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid, 455.

[7] D. Bevington, The Necessary Shakepeare,711.

[8] D. H. Richter, The Critical Tradition, 438.

[9] W. Scott, “Macbeth’s—And Our—Self-Equivocations” (Shakespeare Quarterly: 1986), 160-174.

[10] Ibid, 171.

[11] I am referring here to 2.1.17-18: “Being unprepared, / Our will became the servant to defect”.

[12] Russ McDonald reminds us that hamartia would be “a term more properly understood as an error in action rather than as fatal weakness of character”. The Bedford Companion, 88.

[13] Quotes from Freud are collectively taken from “The ‘Uncanny’” in The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, ed. David H. Richter (Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin’s: 2007), 514-532.

[14]Ibid, 522.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid, 523

[17] See Juliet’s soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in The Necessary Shakespeare ed. D. Bevington (The University of Chicago: 2013), 3.2.5

[18] D. Bevington, 712.

[19] Ibid, 713.

[20] K.K. Cheung, “’Dread’ in Macbeth” (Shakespeare Quarterly: 1984), 431.

[21] S. Freud, 522.

[22] W. Scott, 170.

[23] The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Joseph Campbell Foundation: 2008), 11

[24] Ibid.

[25] S. Freud, 523.

[26] Macbeth is certainly made terrified by this statement, saying “it hath cowed my better part of man” (5.8.18).

[27] D. Bevington, 713

[28] For Macduff has also suffered loss: the death of his wife and children.

[29] Not coincidentally, Macbeth uncannily tries to refuse killing Macduff: “Of all men else I have avoided thee” (5.8.5). He sees a vision of a more perfect and unsullied self in Macduff – to him, there is something of the uncanny in Macduff, something, according to Freud in p. 526, “familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression.” This more perfect and now-alienated self that Macbeth finds in Macduff he has repressed in his murderous drive towards kingship.

[30] The Hero with a Thousand Faces, 21.

DUSK AND THE UNCANNY IN CONRAD’S HEART OF DARKNESS

The dichotomy of Light and Darkness is noticeably prevalent and all-encompassing in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, so much so that the symbolisms and meanings of this antithetical pair may seem at times to fall into ambiguity or to get muddled into complicated significations. Yet the novel remains comfortable with such a situation. Its themes thrive on ambivalence and a tone of seeming uncertainty. What at first glance appears to be a scene of incertitude for characters can turn out to be, after an uncovering of many complex layers, a moment of revelation, self-awareness, or existential understanding. In Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the gulf between Light and Darkness – the gulf that harbours the uncanny, the gulf that represents Dusk – is depicted as a zone wherein Marlow experiences self-realisation and enlightenment.

There is in Heart of Darkness a gap in the dichotomy of Light and Darkness. This gap is magnified and made observable by the distinct contrast in the representative figures of Light and Darkness, and indeed they are portrayed to be almost archetypal. Kurtz is said to be “claimed” by “powers of darkness” (1989). The darkness embodied in Kurtz is universalised as Marlow describes the last moments of his life: “The brown current ran swiftly out of the heart of darkness, bearing us down towards the sea…and Kurtz’s life was running swiftly too, ebbing, ebbing out of his heart into the sea of inexorable time” (2003). The juxtaposition of these sentences parallels Kurtz’s heart with the “heart of darkness” that is found everywhere from the centre of the wilderness to which the phrase alludes, to the River Thames which it threatens to encompass. Kurtz’s position as a figure that embodies darkness is further solidified when he is described in his deathbed as not being able to see the “light…within a foot of his eyes” (2004). Indeed, his stare “could not see the flame of the candle, but was wide enough to embrace the whole universe, piercing enough to penetrate all the hearts that beat in the darkness” (2005). The irony of this description is in Kurtz’s inability to see light no matter how wide or universal his stare is. All he is able to see is darkness, and that darkness resides within him.

Inasmuch as Kurtz is unable to see the light, the Intended is ignorant of – if not unable to comprehend – the darkness in Kurtz. She is portrayed as an archetype of light and of what is beautiful, pure, and innocent. Marlow describes her thus: “She struck me as beautiful—I mean she had a beautiful expression. I know that the sunlight can be made to lie too, yet one felt that no manipulation of light and pose could have conveyed the delicate shade of truthfulness upon those features” (2007). She has “a pale head”, “fair hair”, a “pale visage”, and a “pure brow” (2007). All these fair and beautiful external features set her up in contrast with the darkness within Kurtz. However, her innocence, her “unextinguishable light of belief and love” (2008), is thought by Marlow to be incapable of understanding or bearing the reality of Kurtz’s darkness. He says that, for her, it would be “too dark altogether” (2010). He thus implies that there is a necessary separation between the dealings of Light and Darkness.

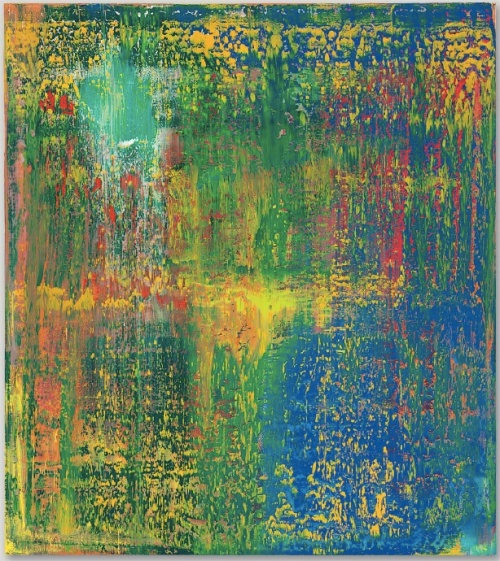

Following Marlow’s logic for separation, it would seem that the Darkness and Light that Kurtz and his Intended signify respectively have between them an unbridgeable gulf. And yet the novel complicates this distinction. Dusk, a time that rests between the bright and dark hours of the day, is depicted in the beginning of the novel with poignancy: “And at last, in its curved and imperceptible fall, the sun sank low, and from glowing white changed to a dull red without rays and without heat, as if about to go out suddenly, stricken to death by the touch of that gloom brooding over a crowd of men” (1955). It is in the light of this setting sun where the Nellie’s crew go through a contemplative and aesthetic experience: “We looked at the venerable stream not in the vivid flush of a short day that comes and departs for ever, but in the august light of abiding memories” (1955). It is also in the climate of this setting wherein Marlow’s narrative is unfolded: not in the brilliance of midday nor in the darkness of midnight, but in the dying light of dusk.

Dusk is the gulf between Light and Darkness, and this gulf may be equated to the realm of the uncanny, the realm of Freud’s Unheimlich. Indeed, insofar as Freud’s concept of the Unheimlich breaks down the binary boundaries between its own essence and that of the Heimlich, so does the concept and imagery of dusk break down the dichotomy of Light and Darkness. This area of the uncanny in the novel breaks down oppositions in such a way that there is certainty to be found in uncertainty and realisation in ambiguity. The gulf of the uncanny, the gap symbolised by dusk, is a dialectical realm wherein the ethos of Marlow’s character attains an understanding of its existence and that of the world and people around him. The culmination of Marlow’s experience, being a character situated symbolically in such a realm, is described by himself as such: “It seemed somehow to throw a kind of light on everything about me—and into my thoughts. It was sombre enough too—and pitiful—not extraordinary in any way—not very clear either. No, not very clear. And yet it seemed to throw a kind of light” (1958). In his experiences are fragments of self-realisation, revelations, and understandings, not least of which is his understanding of Kurtz’s darkness and his Intended’s sparkle of sublimity. Marlow also explains to his fellow seamen that “it seems to me I am trying to tell you a dream…No, it is impossible; it is impossible to convey the life-sensation of any given epoch of one’s existence” (1973). His contemplations and philosophies, unclear to himself at first, are constantly deconstructed and reconstructed in the course of his journey and his narrative.

Marlow is subsequently elevated into a state of enlightenment. He becomes representative of the individual who beholds the Truth and escapes the Platonic Cave, but who also consequently becomes alienated from his company. By the end of the novel he is said to have “ceased, and sat apart, indistinct and silent, in the pose of a meditating Buddha” (2010). And indeed he has already recognised his isolation in the artistic frame when he states, “We live, as we dream—alone” (1973). Yet this alienation, this dream-like uncanny state of retrospection, allows Marlow to observe and understand the universal darkness while remaining apart from it. He thereby becomes the didactic Individual, a signifier of the Particular marked especially by his contrast with the nameless Others, his fellow seafarers, to whom he shares his profound reflections on Truth and the human soul. In this perspective he is not alone. His life, as in his dream-like narration, is recounted with company. Together, they journey through the river of experience and past memories, with the threat of the looming darkness making their quiet solidarity all the more poignant.

Bibliography:

Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. The Longman Anthology of British Literature, ed.by K. J.H. Dettmar, Pearson Education, 2010. pp.1949-2010.

Leave a comment

Filed under Fantasy

Tagged as aesthetics, books, commentary, conrad, darkness, dreams, dusk, essay, freud, heart of darkness, human soul, humanity, imagery, light, literature, marlow, philosophy, reads, ships