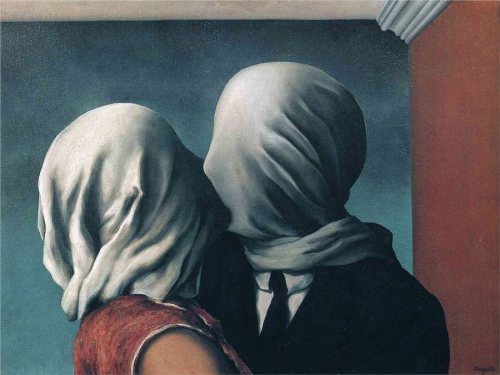

Death and desire are two concepts and realities that greatly concern psychoanalytical and philosophical minds. Their enigmatic natures open up opportunities for various questions, answers, and interpretations concerning their relationship not only between one another, but also with human nature. What roles do both death and desire play in human thought and activity? How do they affect our sense of self, as well as our perception, reception, and interactions with others? Freud’s theories, specifically those found in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), attempt to make sense of death’s interplay with pleasure and desire. The art world, too, has been endeavoring to contemplate and represent such ideas within (and, in some instances, with-out) the context of their cultural and historical roots. René Magritte’s The Lovers (oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 28 7/8″, 1928) depicts the drive of desire as a distortion of the “death-drive,” consequently invoking a sense of the “uncanny” through its manifestation of the “double,” the return of the repressed, and the “compulsion to repeat.” Freud’s work on “The Uncanny” (1919) will help us unveil the psychoanalytical implications of Magritte’s work.

The Lovers’s most striking feature is its depiction of what Freud calls the “double.” In the “phenomenon of the ‘double,’” Freud explains that “we have characters who look alike…so that one possesses knowledge, feelings and experience in common with the other.”[1] The two figures in the painting – the “lovers” – though distinctly gendered in their attire, are made to appear similar to each other in countenance through the cloth(s) that conceal(s) their faces. Indeed, the lovers are necessarily gendered through their clothing in order to display an expression of desire in their contact with each other. In this way, they are made to represent one aspect of the “double”: they become “an insurance against the destruction of the ego.”[2] Moreover, while the lovers do manifest “an ‘energetic denial of the power of death’”[3], they simultaneously portray another, characteristically opposing aspect of the “double.” The double, Freud writes, “from having been an assurance of immortality…becomes the uncanny harbinger of death”[4]. Thus, the lovers, while daringly expressing desire, face the inevitability of eventual death through suffocation. Their desires, in this light, become constrained by death both in a physical and a symbolical sense. The uncanny nature, then, of the figures as “doubles” emanates an anxiety of death consuming the lovers in their display of desire.

Moreover, The Lovers further heightens this anxiety through its depiction of the “return of the repressed”. The “return of the repressed” is “the frightening element” which shows itself “to be something repressed which recurs.”[5] The uncanny feeling of “the return of the repressed” is, as Freud explains, “in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression.”[6] In the case of The Lovers, the “return of the repressed” is not overly much of a return as much as a recurring, or even a re-emerging of the death-drive which underlies every unconscious human thought. The lovers’ drive for desire obliquely coincides with their death-drive: the very expression of their desire, their mutual contact, is that which also emphasises the presence of death. In this light, The Lovers becomes an image that speaks to the irrepressibility of the death-drive. Thus, inasmuch as the desire manifested by the figures in the painting is a representation of the supposed dominance of the “pleasure principle”, so does their physical proximity – and, with it, the painting’s focal point – coincidingly accentuate the shrouding and threatening presence of death. Yet the figures arguably do not show any struggle to remove themselves from their doom-laden pose. It is because their sense of the pleasure principle – that is to say, their sense of desire – is at one with the death-drive, and, indeed, this affect of desire becomes a form of the death-drive.

To better understand why this is, it is of principal importance to observe further that the lovers express an uncanny “compulsion to repeat.” According to Freud, “it is possible to recognize the dominance in the unconscious mind of a ‘compulsion to repeat’ proceeding from the instinctual impulses and probably inherent in the very nature of the instincts – a compulsion powerful enough to overrule the pleasure principle.”[7] In The Lovers, the compulsion to repeat works to free the death-drive from the repressive impulses of the pleasure principle. There is a hint of irresistibility in the lovers’ pose: their lack of struggle to break free from their kiss despite their heads being wrapped in cloth marks their uncannily calm demeanour. Moreover, inasmuch as the binary boundary between the heimlich and the unheimlich is, as Freud hints, eventually broken down so that the “heimlich…finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich”[8], so much so is the boundary that divides the pleasure principle and the death-drive distorted, as the viewers are left to feel uncertain about whether the lovers’ primary drive is that of Eros or that of Thanatos. Thus, there is in The Lovers the inevitability of the viewer’s intellectual and emotional uncertainty regarding both the affect of desire and the anxiety of death – an uncertainty that allows the painting to radiate an overall feeling of uncanniness.

Ultimately, The Lovers prompts questions concerning the relationship between death and desire. The uncanny elements it embodies serve to make audiences obliquely contemplate over such a relationship. The presentation of the “double”, which juxtaposes themes of death and desire, points out to the ever-looming presence of death. Its depiction of the return of the repressed and the compulsion to repeat underscores the dominance of the death-drive in its unrepressed form. A Freudian reading, then, as we have seen, effectively brings out key themes from the painting – but it would be as interesting to see what Lacan or even the existentialist philosophers have to say in response.

Bibliography:

René Magritte, The Lovers, 1928, Oil on canvas, 21 3/8 x 28 7/8″ (54 x 73.4 cm)

Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny.” In The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, edited by David H. Richter, 514-532. Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin’s, 2007.

[1] Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny,” in The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, edited by David H. Richter (Boston: Bedford/ St. Martin’s, 2007), 522.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] p. 523.

[5] p.526.

[6] Ibid.

[7] p. 524.

[8] p. 518.